Website: www.lawrencecoates.com

Workshop title: The Story and the Novel--Forms and Variations

June 4, Opening Faculty Panel: Why are we writing?

Lawrence commented that some people write from tragedy and pain (I would count myself in that group), but that he writes primarily out of inquiry, out of not necessarily accepting what's taken to be "real." He writes historical novels. Writing is a means of understanding the self as one of many; of locating the stories of others; of exploring how people live in relation to the natural world in the place he comes from. Similar to Ellen Bass (and her comment picked up from Lawrence's), Lawrence says writing is about the pleasure of making.

What I learned about Lawrence's workshop from my "spies"

Well, I didn't have any official spies that I grilled about the fiction workshop. We heard from several participants during Open Mic readings, and I was moved, entertained and impressed by what I heard. Fiction writers create worlds without hanging on to actually occurring or already occurred realities. In my own writing (so far) I remain so connected to rendering actual events that this ability to create worlds is a marvel to me. I read a good deal of fiction, but I wonder if I will ever grow the muscles to write it.

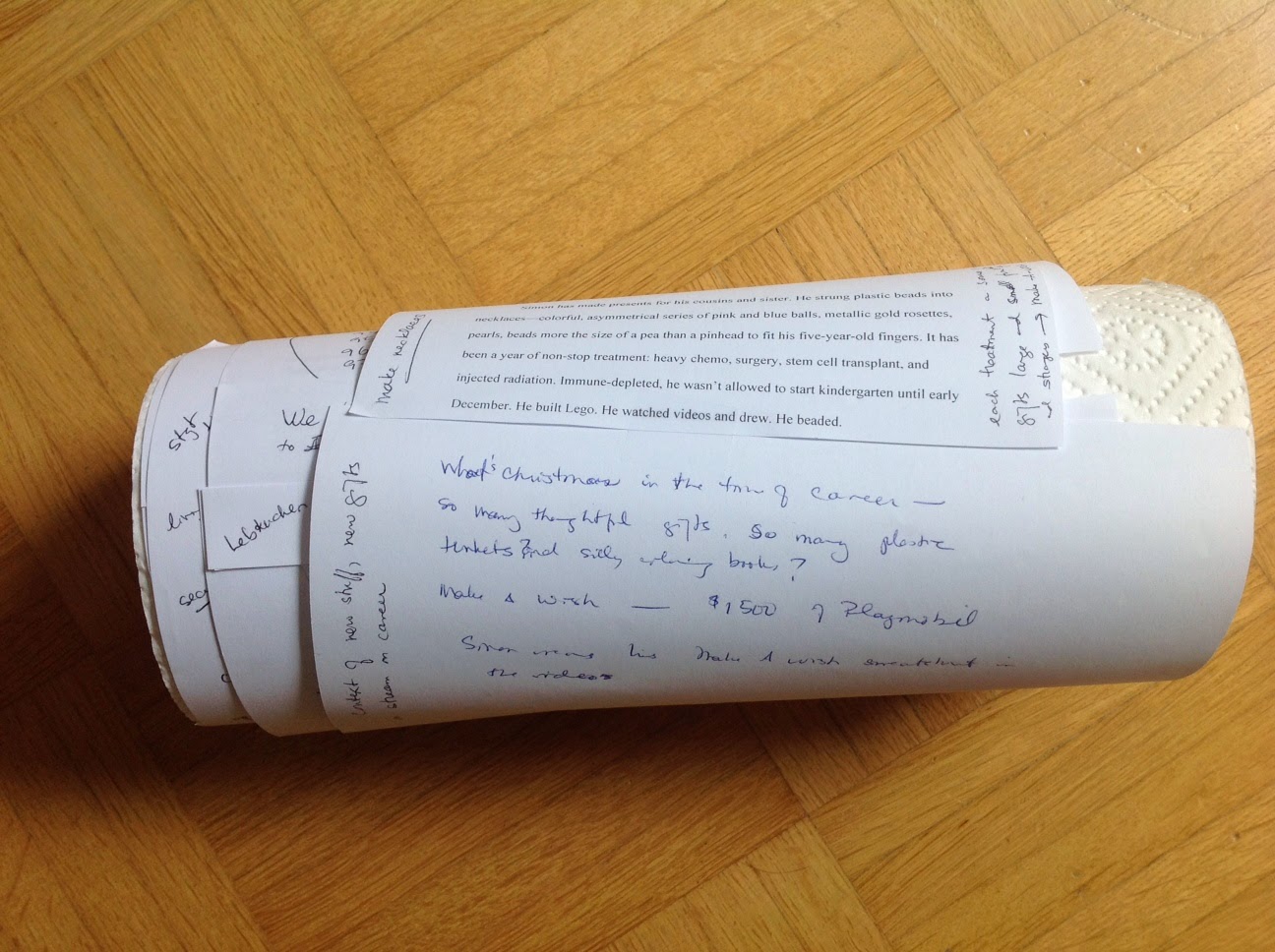

Despite the lack of spy activity, I have located one of the fiction workshop activities based on texts Lawrence shared during his reading and in a posting he made on Facebook right after the conference. He described the exercise as picking an improbable image to write to. The images are generated by a group of writers together. Then each picks one to write about in 500 words. I'm sure if you try one of these prompts, he'd be delighted to hear from you.

From a June 9, 2014 Facebook post by Lawrence Coates:

"If anyone who has done a common image story with me is interested, my group came up with three new prompts at Writers @ Work. The rules are simple... you have to write a short short, 500 words or less, with one of these images included:He's right, "Lobster in the Laundromat" made an impression on me and others. I've looked for a published version to link to, but I haven't turned one up yet. My current lead is a literary magazine called Lake Effect. However, it is print only, and the website does not indicate the issue that contains the Lobster story. I'll update this entry when I get the information.

1) Baby doll in a wheelchair.

2) Panties in a pine tree

3) Pizza in the rain.

It seems that one of the shorts I read there, 'Lobster in the Laundromat,' made an impression. At least, one of the other faculty members said that his students were talking about it."

June 6, Reading by Lawrence Coates on Friday night

Lawrence opened his reading with two of these short shorts. The first, "Bats in Purses" and the second, "The Lobster in the Laundromat." Both pieces carried compelling and bizarre imagery. It stays with me, the picture of a lobster watching clothes circle around beyond the glass door of a washer. The good news is that another piece, The Trombone in the Shopping Cart, was just published by Ascent. It's different from the Lobster, but the stories share an aching loneliness--the loneliness of being overlooked--that pierced me when I listened to the reading.

During the second part of his reading, Lawrence read the first chapter of his newest novel, The Garden of the World. While researching a previous novel, he'd come across an historical event that he chose to be the ending of this novel. (I won't say what the event was; you might find it more interesting to discover for yourself.) He conceded that some of the research for this winemaking novel was "liquid and pleasurable." When he mentioned the "fruiting canes" of the grape vines in the second paragraph, I became alert: here was my chance to learn English terminology about vineyards, since I've learned most of it in German.

This novel was the Coates book I purchased. I started it on the airplane home and finished it a few days ago. The pages are filled with sweeping and intimate scenery, with period detail in buildings, clothing and vehicles, and with characters that fully inhabit three dimensional space. Most of the chapters are subdivided into morsels of scene and image. The events accumulate in a way that feels close to life--memorable segments add up while the stuff in between fades away. There's lightness in the language--not in the sense of lacking content but in the sense of moving easily, without being weighted down. Here's a sample from a World War I battlefield in Chapter Two "Loyalty Day" (page 17):

"There was only one tree still standing in the cratered earth between the two trenches, a stumpy, unidentifiable tree, with most of its branches and leaves blown off, more like the memory of where a tree had been than anything yet living. ...June 8, Closing faculty panel: How we got here and where do we go from here?

Then, suddenly, the tree was lit from within, a great tower of light from in the heart of it, illuminating it to the tip of its crippled branches. Gill remembered very clearly that sudden light."

Bouncing off Ellen Bass' comment about looking for multiple metaphor options (rather than aiming at some ultimately "right" one), Lawrence shared a technique he uses to get clarity about a character. Define the character by generating ideas this way: "S/he's the kind of person who _____________." Like metaphor, these ideas need to stay on the level of the concrete. He gave an example of the character Meyer Wolfsheim in the Great Gatsby, a man who wears cuff links made of human molars.

As a favorite exercise, Lawrence offered the disparate image activity described above. Another image possibility: Wedding Cake in the Road. Although I haven't tried it yet, the exercise reminds me of a prompt I've tried from Brian Kiteley's 3A.M. Epiphany. This link to Kiteley's website will direct you to some exercises from his new book, the 4A.M. Breakthough. Similar concept. Exercise 15 in the 3A.M. Epiphany instructs the writer 1) to develop a vivid, haunting image; 2) to develop a second, unrelated compelling image; 3) to write a story fragment out of the two images together (600 words). I was astonished at the energy of this when I tried it several years ago. I'm guessing the disparate image idea has a similar source of tension and creativity.

I'm always grateful for creative impulses from fiction writers and especially from writers as generous and pleasant as Lawrence Coates.